Understanding Food Allergies and Intolerances (They’re not the same!)

Food allergies and food intolerances are new to almost no one. Most know about the common struggles and discomfort that each of these bring, but not many know about the differences between allergies and intolerances and the difficulties of treating each. Here’s our basic guide to understanding food allergies, food intolerances, and more.

What are food allergies?

Food allergies, although they seem incredibly common, only affect about 1-2% of the adult population and up to 6% of children [1]. Common food allergies include peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, and shellfish. Symptoms can vary in type, location in the body, severity, duration and more.

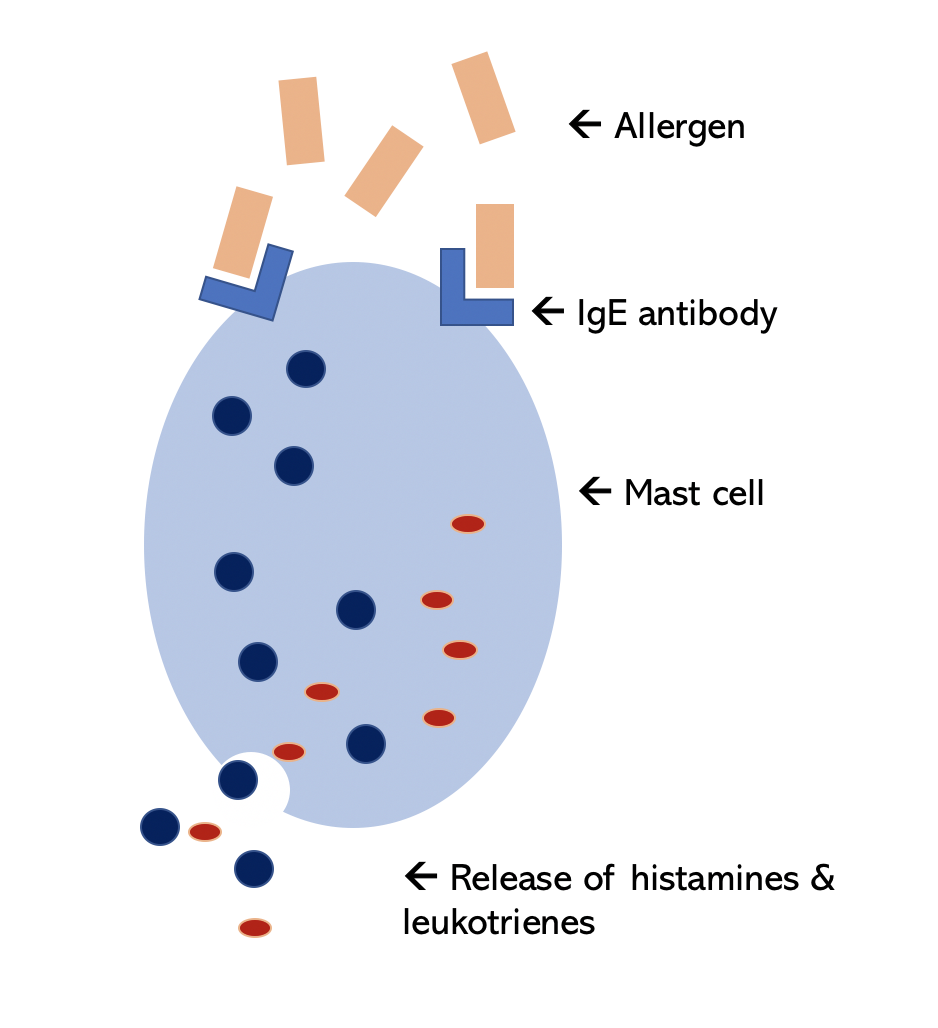

Food allergies can be seen as the body’s defense mechanism acting in response to foods that, under normal circumstances, do not produce reactions. In those who do have allergic reactions, the immune system recognizes certain protein signals on the food, which the body then sees as the foreign invader [9]. The molecule that recognizes these protein signals is called an “antibody” or “immunoglobulin” (Ig), in this case IgE. This causes allergic reactions in some food sensitive people as the body tries to “eliminate” the food that it sees as foreign.

Common symptoms are usually gastrointestinal (GI) or cutaneous (related to the skin). The gastrointestinal tract lining is your digestive system’s barrier between the outside environment and the body’s internal processing space for absorbing nutrients from food. Allergic inflammation in the GI barrier can cause discomfort through symptoms like diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain [2]. Cutaneous symptoms can include acute urticaria (hives), angioedema (fluid swelling beneath the skin) and contact dermatitis after handling food (presents as red itchy rash on skin but is not contagious). Experiencing respiratory symptoms as a result of food allergy is less common, but symptoms can include food-induced nasal congestion, runny nose and wheezing [3]. Food allergy symptoms are due to the release of naturally occurring histamine. Histamine is produced by mast cells that live in different tissues of our bodies. Mast cells are usually found at interfaces where the body meets the outside environment, for example in the lungs, nose, eyes, or skin. When a substance from the environment reaches the barrier and is recognized as foreign, the IgE on the surface of the mast cell binds the allergen [10], allowing for activation of mast cells that release histamine and other allergic inflammatory chemicals, such as leukotrienes that amplify the allergic response.

Oral allergy syndrome is easy to confuse with a food allergy, but there are important differences. Oral allergy syndrome often occurs in individuals who already experience seasonal allergy symptoms (itchy eyes, itchy nose, nasal congestion). Their bodies undergo allergic reaction in the presence of pollen in the air. In oral allergy syndrome, certain food proteins cross-react with pollen proteins, telling the body to react as if you were eating the pollen itself. Symptoms are usually limited to itching or swelling on or around the mouth and resolve themselves with time. Treatments often include avoidance of certain foods. Common cross-reacting pollen-food pairs include:

- Ragweed pollen cross-reacts with bananas, cucumbers, melons, sunflower seeds, zucchini

- Grass pollen cross-reacts with celery, melons, oranges, peaches, tomato

- Birch pollen cross-reacts with apple, almond, carrot, celery, cherry, hazelnut, kiwi, peach, pear, plum

What are food intolerances?

Food intolerances create a reaction using a different mechanism than allergies. Food intolerances do not operate through the IgE antibody, but instead by pharmacologic or toxic substances in the food or other non-IgE immune mechanisms [9]. For example, touching or ingestion of external sources of histamine (like spoiled or poorly refrigerated fish) can cause allergy-like symptoms. This is a form of pharmacological reaction rather than actual allergy to fish [5].

Another more common example of a food intolerance is lactose intolerance, making it difficult to consume cow’s milk daily products (like cheese or ice cream). Again, this is not due to an IgE-mediated reaction but rather due to a digestive enzyme, lactase, that some individuals do not have. Treatments for lactose intolerance include avoidance of dairy, using no-lactose alternatives, or lactase supplements.

Some other common non-allergic food intolerances include sensitivities to carbohydrates (specifically to fermentable oligo- di- monosaccharide polyols, also known as FODMAPs) or gluten, a common protein found in rye, barley, oats, wheat and more. Sensitivity to these can induce gastrointestinal symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and more [1].

Celiac disease (CD) is a specific immune disorder that can also cause discomfort and pain after eating gluten. When a patient with CD eats gluten, the body produces an immune response on itself in order to try and eliminate the gluten that it sees as foreign. CD is often misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome or wheat intolerance/sensitivity. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is also an example of a common food intolerance that can cause abdominal cramping, bloating, and bowel irritation. IBS can also be triggered by highly fatty meals, coffee, alcohol, excessive fructose or sorbitol (two types of sugar). These symptoms are again related more to digestive system reactions rather than immune system reactions. CD is also hereditary, meaning it is passed through families. Treatment includes changing to a gluten-free diet. Although some symptoms may be similar, CD is different from wheat intolerance (non-Celiac gluten disease) which is also different from wheat allergy. Non-Celiac gluten disease (NCGD), or non-Celiac wheat sensitivity, is neither an autoimmune disorder (like CD) nor an IgE-mediated immune reaction (like wheat allergy). Treatment usually also includes identifying the threshold amount of gluten to initiate symptoms and avoidance of gluten. Wheat allergies are IgE-mediated allergic reactions to wheat allergens.

How do you test for food allergies and intolerances?

The current gold standard for food allergy testing is conducting a double-bind placebo-controlled trial [1], which is a way to clinically rule out or rule in specific food allergies. However, this is an expensive and time-consuming process and is not always feasible. A food challenge can also be done by eating small amounts of specific foods under clinical supervision and watching for reactions. More practically, skin prick tests can be used to test for allergies. Skin testing determines whether the allergic symptoms are due to presence of allergen-specific IgE antibodies [7].

How do you treat food allergies and intolerances?

The first method and most common starting point is often avoidance of certain foods from the individual’s diet and patient education about how to do so. Patients can work with dieticians to ensure they are not over-restricting themselves in their diet. Medication can be used to mitigate symptoms. In the case of accidental exposure leading to severe reactions, adrenaline/epinephrine (such as an EpiPen) or antihistamines should always be available.

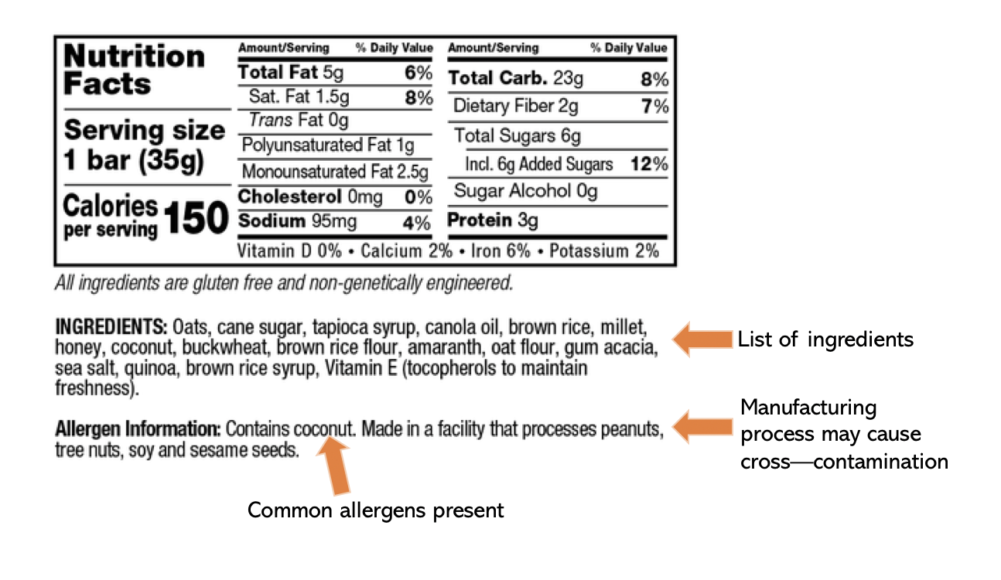

Understanding how to read food labels and recognizing uncommon names for ingredients is critical to successful avoidance of specific allergens. For example, gluten is found in many common foods, including wheat, oats, barley, brown rice and rye. Gluten may also be found in beer, soy sauce, teriyaki sauce, and broth. It is always good to check with the manufacturer or chef if you are unsure about whether something has gluten in it or not, either as an ingredient or through potential cross-contamination. Gluten alternatives usually include almond flour, buckwheat flour and coconut flour. If the food’s ingredients say “Gluten-Free” then the product is usually safe (FDA labels gluten-free as foods with less than 20ppm gluten present). However, it is important to remember that “wheat-free” is not the same as gluten-free. Check the rest of the ingredients to make sure there are no hidden allergens.

Lactose, like gluten, also comes in many less-recognized forms. Lactose, whey and casein are all major components of milk and dairy, meaning that isolation of whey or casein proteins can still contain lactose. Usually lactose is only present in small amounts, but for those with severe lactose intolerance, whey and casein should still be avoided. Whey is popular as a dry protein powder, so many individuals with lactose intolerance turn to non-dairy protein powders like soy or pea protein. Lactose can also be found in medications, such as vitamin D pills or birth control. Although it is usually found in small amounts, it would be best to check with your doctor before using lactose-containing medication if you are intolerant.

In some cases, desensitization to the food allergen can occur. For example, peanut allergies can be weakened using oral immunotherapy, which controls exposure to peanuts overtime with the goal of increasing the threshold of peanut ingestion before reaction. This is done in an allergist’s office equipped to treat anaphylaxis. The patient should also continue to carry epinephrine because this is not a cure for food allergy.

Recent

Popular